1880 Democratic National Convention on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1880 Democratic National Convention was held June 22 to 24, 1880, at the Music Hall in

Samuel Jones Tilden began his political career in the " Barnburner," or Free Soil, faction of the New York Democratic Party. He was a successful lawyer and had accumulated a considerable fortune. A disciple of former president

Samuel Jones Tilden began his political career in the " Barnburner," or Free Soil, faction of the New York Democratic Party. He was a successful lawyer and had accumulated a considerable fortune. A disciple of former president

One beneficiary of Tilden's departure from the scene was Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was the scion of an old political family in Delaware and had represented his state in the United States Senate since 1869. As one of a relative handful of conservative Democrats in the Senate at the time, Bayard began his career opposing vigorously, if ineffectively, the Republican majority's plans for the

One beneficiary of Tilden's departure from the scene was Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was the scion of an old political family in Delaware and had represented his state in the United States Senate since 1869. As one of a relative handful of conservative Democrats in the Senate at the time, Bayard began his career opposing vigorously, if ineffectively, the Republican majority's plans for the

File:StephenField.png, Associate Justice

The delegates assembled on June 22, 1880, at Cincinnati's Music Hall. The venue was a large, red brick building in the

The delegates assembled on June 22, 1880, at Cincinnati's Music Hall. The venue was a large, red brick building in the

Illinois was the next state to offer a name, as former Representative

Illinois was the next state to offer a name, as former Representative

The clerk called the roll of the states again, and a band played "

The clerk called the roll of the states again, and a band played "* The candidate was not formally nominated.

File:1880DemocraticPresidentialNomination1stBallotBefore.png,

File:1880DemocraticPresidentialNomination1stBallotAfter.png,

File:1880DemocraticPresidentialNomination2ndBallotBefore.png,

File:1880DemocraticPresidentialNomination2ndBallotAfter.png,

Turning to other matters, the delegates listened as

Turning to other matters, the delegates listened as

online

Website *

Democratic Party Platform of 1880

''The American Presidency Project''. {{Authority control 1880 conferences 1880 United States presidential election 1880 in Ohio 19th century in Cincinnati Conventions in Cincinnati Political conventions in Ohio Ohio Democratic Party Political events in Ohio Democratic National Conventions June 1880 events

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, and nominated Winfield S. Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

for president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and William H. English

William Hayden English (August 27, 1822 – February 7, 1896) was an American politician. He served as a U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1853 to 1861 and was the Democratic Party's nominee for Vice President of the United States i ...

of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

for vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

in the United States presidential election of 1880.

Six men were officially candidates for nomination at the convention, and several more also received votes. Of these, the two leading candidates were Hancock and Thomas F. Bayard

Thomas Francis Bayard (October 29, 1828 – September 28, 1898) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat from Wilmington, Delaware. A Democrat, he served three terms as United States Senator from Delaware and made three unsuccessful bids ...

of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. Not officially a candidate, but wielding a heavy influence over the convention, was the Democratic nominee from 1876, Samuel J. Tilden of New York. Many Democrats believed Tilden to have been unjustly deprived of the presidency in 1876 and hoped to rally around him in the 1880 campaign. Tilden, however, was ambiguous about his willingness to participate in another campaign, leading some delegates to defect to other candidates, while others stayed loyal to their old standard-bearer.

As the convention opened, some delegates favored Bayard, a conservative Senator, and some others supported Hancock, a career soldier and Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

hero. Still others flocked to men they saw as surrogates for Tilden, including Henry B. Payne

Henry B. Payne (November 30, 1810September 9, 1896) was an American politician from Ohio. Moving to Ohio from his native New York in 1833, he quickly established himself in law and business while becoming a local leader in Democratic politics. ...

of Ohio, an attorney and former representative, and Samuel J. Randall of Pennsylvania, the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. The first round of balloting was inconclusive. Before the second round, Tilden's withdrawal from the campaign became known for certain and delegates flocked to Hancock, who was nominated. English, a conservative politician from a swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pres ...

, was nominated for vice president. Hancock and English were narrowly defeated in the race against Republicans James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

and Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James ...

that autumn.

Issues and candidates

In 1876,Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

defeated Democrat Samuel J. Tilden of New York in the most hotly contested election to that time in the nation's history. The results initially indicated a Democratic victory, but the electoral votes of several states were ardently disputed until mere days before the new president was to be inaugurated. Members of both parties in Congress agreed to convene a bi-partisan Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

, which ultimately decided the race for Hayes. Most Democrats believed Tilden had been robbed of the presidency, and he became the leading candidate for nomination in 1880. In the meantime, issues of tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

reform and the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

divided the country and the major parties.

The monetary issue played a large role in selecting the nominees in 1880, but had little effect on the general election campaign. The debate concerned the basis for the United States dollar's value. Nothing but gold and silver coin had ever been legal tender in the United States until the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, when the mounting costs of the war forced Congress to issue " greenbacks" ( dollar bills backed by government bonds). They paid for the war, but resulted in the most severe inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

seen since the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. After the war, bondholders and other creditors (especially in the North) wanted to return to a gold standard. At the same time, debtors (often in the South and West) benefited by the way inflation reduced their debts, and workers and some businessmen liked the way inflation made for easy credit. The issue cut across parties, producing dissension among Republicans and Democrats alike and spawning a third party, the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

, in 1876, when both major parties nominated hard money men. Monetary debate intensified as Congress effectively demonetized silver in 1873 and began redeeming greenbacks in gold by 1879, while limiting their circulation. By the 1880 convention, the nation's money was backed by gold alone, but the issue was far from settled.

Debate over tariffs would come to play a much larger role in the campaign. During the Civil War, Congress raised protective tariffs to new heights. This was done partly to pay for the war, but partly because high tariffs were popular in the North. A high tariff meant that foreign goods were more expensive, which made it easier for American businesses to sell goods domestically. Republicans supported high tariffs as a way to protect American jobs and increase prosperity. Democrats, generally, saw them as making goods unnecessarily expensive and adding to the growing federal revenues when, with the end of the Civil War, that much revenue was no longer needed. Many Northern Democrats supported high tariffs, however, for the same economic reasons that their Republican neighbors did, so while Democratic platforms called for a tariff "for revenue only," their speakers avoided the question as much as possible.

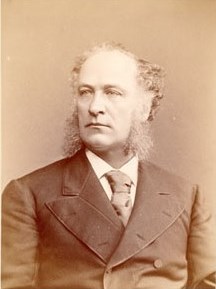

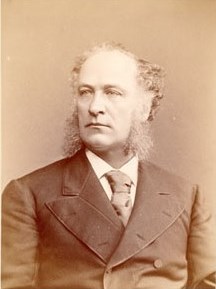

Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden began his political career in the " Barnburner," or Free Soil, faction of the New York Democratic Party. He was a successful lawyer and had accumulated a considerable fortune. A disciple of former president

Samuel Jones Tilden began his political career in the " Barnburner," or Free Soil, faction of the New York Democratic Party. He was a successful lawyer and had accumulated a considerable fortune. A disciple of former president Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, Tilden was first elected to the New York State Assembly in 1846. Tilden defected with Van Buren to the 1848 Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

convention before returning to the Democratic party after the election. Unlike many free-soil Democrats, Tilden stayed with his party in the 1850s instead of transferring his allegiance to the newly formed Republican party. When the Civil War began, he remained loyal to the Union and considered himself a War Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

. In 1866, he became chairman of the New York State Democratic party, a post he held for eight years. Tilden initially cooperated with Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

, the New York City political machine of William "Boss" Tweed, but the two men soon became enemies. In the early 1870s, as reports of Tammany's corruption spread, Tilden took up the cause of reform. He formed a rival faction that captured control of the party and led the effort to uncover proof of Tammany's corruption and remove its men from office. Tweed was soon indicted and convicted; Tammany was weakened and reformed, but not vanquished.

The triumph over Tammany paved the way for Tilden's election to a two-year term as governor in 1874. As a popular, reformist governor of a large swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pres ...

, Tilden was a natural candidate for the presidency in 1876, when one of the main issues was the corruption of the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. He was nominated on the second ballot, and campaigned on a platform of reform and sound money (i.e. the gold standard). His opponent was Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, likewise noted for his honesty and hard-money views. After the closely contested election, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the dispute to a bipartisan Electoral Commission, which would determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes. Tilden opposed the idea, but many Democrats supported it as the only way to avoid a second Civil War. The commission voted 8–7 to award Hayes the disputed votes. Congressional Democrats acquiesced in Hayes's election, but at a price: the new Republican president withdrew federal troops from Southern capitals after his inauguration. Tilden was defeated—robbed, in his opinion and that of his supporters.

Tilden spent the next four years as the presumptive Democratic candidate in 1880. In 1879, he declined to run for another term as governor and focused instead on building support for the 1880 presidential nomination. He considered many of his former friends (including Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware) enemies now for their support of the Electoral Commission, and sought to keep the "fraud of '76" in the spotlight and burnish his own future candidacy by having his congressional allies investigate the events of the post-election maneuvering. For ten months beginning in May 1878, the Potter Committee, chaired by Democratic Congressman Clarkson Nott Potter

Clarkson Nott Potter (April 25, 1825 – January 23, 1882) was a New York attorney and politician who served four terms in the United States House of Representatives from 1869 to 1875, then again from 1877 to 1879.

Early life

Potter was born in ...

of New York, investigated allegations of fraud and corruption in the states which had contested electoral votes in 1876. Rather than produce conclusive evidence of Republican malfeasance, as Tilden's supporters hoped, the committee exonerated Tilden of wrongdoing, but uncovered conflicting evidence that showed state election officials of both parties in an unfavorable light. This, and Tilden's declining health, made many Democrats question his candidacy. Even so, Tilden's presumed ability to carry New York, combined with his political organization and personal fortune, made him a serious contender.

The first of these qualifications was shattered with the Republican victory in the New York gubernatorial election in 1879. In that election, a revitalized Tammany split from the regular Democratic party in a patronage dispute with Tilden's faction (now known as the "Irving Hall Democrats"). Tammany ran its new leader, "Honest" John Kelly, as an independent candidate for governor, allowing the Republicans to carry the state with a plurality of the vote. Tilden began to waver, issuing ambiguous statements about whether he would run again. Rumors circulated wildly in the months before the convention, with no definitive word from Tilden. As the New York delegation left for the national convention in Cincinnati, Tilden gave a letter to one of his chief supporters, Daniel Manning, suggesting that his health might force him to decline the nomination. Tilden hoped to be nominated, but only if he was the unanimous choice of the convention; if not, Manning was entrusted to make the contents of Tilden's letter available to the New York delegation. When it became clear that the nomination would be contested, Manning revealed the contents of the Tilden letter; it was vague and inconclusive, but once is contents became known to Tilden's home state delegates, they chose to interpret it as a withdrawal. The New York delegation now considered Tilden's candidacy to be ended, and sought a new standard-bearer.

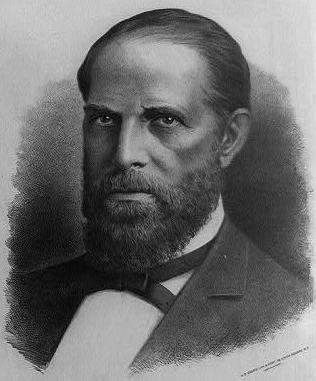

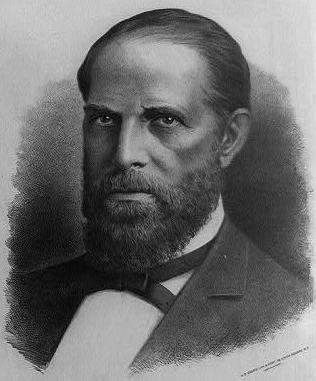

Bayard

One beneficiary of Tilden's departure from the scene was Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was the scion of an old political family in Delaware and had represented his state in the United States Senate since 1869. As one of a relative handful of conservative Democrats in the Senate at the time, Bayard began his career opposing vigorously, if ineffectively, the Republican majority's plans for the

One beneficiary of Tilden's departure from the scene was Senator Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware. Bayard was the scion of an old political family in Delaware and had represented his state in the United States Senate since 1869. As one of a relative handful of conservative Democrats in the Senate at the time, Bayard began his career opposing vigorously, if ineffectively, the Republican majority's plans for the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

of the Southern states after the Civil War. Like Tilden, Bayard supported the gold standard and had a reputation for honesty. At the 1876 convention, Bayard had placed a distant fifth in the balloting, but supported Tilden's cause in the general election, speaking on his behalf around the country. The political friendship between the two quickly soured in the election's aftermath as Bayard supported the Electoral Commission and Tilden opposed it. Bayard believed the commission was the only alternative to civil war, and served as one of the Democratic members; Tilden took this as a personal betrayal.

In the four years that followed, Bayard sought to build support for another run at the nomination. He and Tilden competed for support among Eastern conservatives because of their support for the gold standard. The gold standard was less popular in the South, but there Bayard stacked his years-long advocacy in the Senate for pro-Southern conservative policies against Tilden's political machine and wealth in the contest for Southern delegates. A blow to Bayard's cause came in February 1880 when the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American online newspaper published in Manhattan; from 2002 to 2008 it was a daily newspaper distributed in New York City. It debuted on April 16, 2002, adopting the name, motto, and masthead of the earlier New York ...

'', a newspaper friendly to Tilden, published a transcript of a speech Bayard made in Dover, Delaware, in 1861. As the states of the Deep South were seceding from the Union, a young Bayard had proclaimed "with this secession, or revolution, or rebellion, or by whatever name it may be called, the State of Delaware has naught to do", and urged that the South be permitted to withdraw from the Union in peace. To many in the South, this confirmed their view of Bayard as their champion, but paradoxically it weakened Bayard's support with other Southerners, who feared that a former Peace Democrat

In the 1860s, the Copperheads, also known as Peace Democrats, were a faction of Democrats in the Union who opposed the American Civil War and wanted an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates.

Republicans started calling anti-war D ...

would never be acceptable to Northerners. At the same time, Bayard's uncompromising stance on the money question pushed some Democrats to support Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, who had not been identified with either extreme in the gold–silver debate and had a military record that appealed to Northerners. As the convention opened, Bayard was still among the leading candidates, but was far from certain of victory.

Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

represented an unusual confluence in the post-war nation: a man who believed in the Democratic Party's principles of states' rights and limited government, but whose anti-secessionist sentiment was unimpeachable. A native of Pennsylvania, Hancock graduated from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

in 1844 and began a forty-year career as a soldier. He served with distinction in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

and in the antebellum peacetime army. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Hancock remained loyal to the Union. He was promoted to brevet brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in 1861 and placed in command of a brigade in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

. In the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, he led a critical counterattack and earned the nickname "Hancock the Superb" from his commander, Major General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

. At Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, he led a division in the Union victory and was promoted to major general. Hancock's shining moment came at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

when he organized the scattered troops, rallied defenses, and was wounded on the third day as his troops turned back Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the ...

.

Since 1864, when he received a single unsolicited vote at the Democratic National Convention, Hancock had been a perennial candidate. As military governor of Louisiana and Texas in 1867, Hancock had won the respect of the white conservative population by issuing his General Order Number 40, in which he stated that if the residents of the district conducted themselves peacefully and the civilian officials performed their duties, then "the military power should cease to lead, and the civil administration resume its natural and rightful dominion." He had a larger following at the 1868 convention, finishing as high as second place in some rounds of balloting. In 1876, Hancock again drew a considerable following, but never finished higher than third place at that year's convention. In 1880, another Hancock boom began, this time centered mostly in the South. In March of that year, the '' New Orleans Picayune'' ran an editorial that called for the general's nomination, partly for who he was—a war hero with conservative political principles—and partly for who he was not—a known partisan of either side of the monetary or tariff debates. As Tilden and Bayard rose and fell in the estimation of Democratic voters, Hancock's bid for nomination gathered steam. Some were unsure whether, after eight years of Grant, himself a former general, the party would be wise to give the nomination to another "man on horseback", but Hancock remained among the leading contenders as the convention began that June.

Other contenders

Several other candidates arrived in Cincinnati with delegates pledged to them. Former RepresentativeHenry B. Payne

Henry B. Payne (November 30, 1810September 9, 1896) was an American politician from Ohio. Moving to Ohio from his native New York in 1833, he quickly established himself in law and business while becoming a local leader in Democratic politics. ...

, an Ohio millionaire, had gathered a number of former Tilden supporters to his cause. Payne was a corporate lawyer and hard money advocate, but also a relative unknown outside Ohio. In April 1880, the '' New York Star'' published a tale that Tilden had bowed out of the race and instructed the Irving Hall faction to back Payne for the presidency. Tilden never confirmed the rumor, but after his letter of June 1880 to the New York delegation, many of his supporters did consider Payne among their likely choices. Payne, like Bayard, had served on the Electoral Commission of 1876, but had nevertheless maintained Tilden's friendship. He maintained his loyalty to Tilden until the convention, when his withdrawal was certain. Payne was hindered by a fellow Ohioan, Senator Allen G. Thurman, who controlled their home state's delegation. Thurman looked like a natural successor to Tilden, as a popular conservative from a swing state with a background as an attorney, but he, like Bayard, had earned Tilden's enmity by serving on the Electoral Commission. Thurman was also less wedded to the gold standard than some Northeastern delegates would tolerate.

Another would-be heir to Tilden was Samuel J. Randall, since 1863 a congressman from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

. Like Tilden, Randall was conservative on the money question but, unusually for a Democrat, he supported high tariffs to protect American industry. He also advocated legislation to reduce the power of monopolies. Tilden had supported Randall in his quest to become Speaker of the House, and Randall returned the favor by remaining a loyal Tilden man up to the convention. He now hoped for the support of the former Tilden adherents in his quest for the presidency. Former Governor Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

of Indiana, Tilden's 1876 running mate, also sought a claim on the previous nominee's support. He came from a crucial swing state that the Democrats had narrowly carried in 1876 and had some support in the Midwestern states. His popularity with delegates from the Northeast was impaired by his views on the currency question; he sided with those who wanted looser money.

Two candidates stood with rather less support. William Ralls Morrison

William Ralls Morrison (September 14, 1824 – September 29, 1909) was a U.S. Representative from Illinois.

Early life and career

Born on a farm at Prairie du Long, near the present town of Waterloo, Illinois, Morrison attended the common sc ...

of Illinois had served in Congress since 1873 and was best known for advocating tariff reductions despite hailing from a protectionist district. He commanded little support outside his home state, and was seen as only a favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

. Justice Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field (November 4, 1816 – April 9, 1899) was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897, the second longest tenure of any justice. Prior to this a ...

of the United States Supreme Court was better known, but still an unlikely contender. The only candidate from the Far West, Field was respected as a scholar of the law, but had greatly diminished his chances with his home state of California by striking down anti-Chinese legislation

Anti-Chinese sentiment, also known as Sinophobia, is a fear or dislike of China, Chinese people or Chinese culture. It often targets Chinese minorities living outside of China and involves immigration, development of national identity in ...

in that state in 1879. Even so, some observers, including Edwards Pierrepont

Edwards Pierrepont (March 4, 1817 – March 6, 1892) was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierre ...

, considered Field a likely choice for the nomination.

Stephen J. Field

Stephen Johnson Field (November 4, 1816 – April 9, 1899) was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897 ...

of California

File:Thomas Andrews Hendricks.jpg, Former Governor Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

of Indiana

File:WilliamRallsMorrison.png, Representative William R. Morrison of Illinois

File:HenryBPayne.png, Former Representative Henry B. Payne

Henry B. Payne (November 30, 1810September 9, 1896) was an American politician from Ohio. Moving to Ohio from his native New York in 1833, he quickly established himself in law and business while becoming a local leader in Democratic politics. ...

of Ohio

File:Samuel J. Randall - Brady-Handy.jpg, Speaker of the House Samuel J. Randall of Pennsylvania

File:AllenGThurman.png, Senator Allen G. Thurman of Ohio

Convention

Preliminaries

The delegates assembled on June 22, 1880, at Cincinnati's Music Hall. The venue was a large, red brick building in the

The delegates assembled on June 22, 1880, at Cincinnati's Music Hall. The venue was a large, red brick building in the High Victorian Gothic

High Victorian Gothic was an eclectic architectural style and movement during the mid-late 19th century. It is seen by architectural historians as either a sub-style of the broader Gothic Revival style, or a separate style in its own right.

Promo ...

style, which had opened in 1878. Intended, as the name suggests, for musical performances, the hall also functioned as Cincinnati's convention center until a separate building was constructed in 1967. William Henry Barnum of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, called the convention to order at 12:38 p.m. An opening prayer was presented by Unitarian minister Charles William Wendte. Then, George Hoadly

George Hoadly (July 31, 1826August 26, 1902) was a Democratic politician. He served as the 36th governor of Ohio.

Biography

Hoadly was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on July 31, 1826. As the son of George Hoadley and Mary Ann Woolsey Hoadley ...

, a Tilden associate and future governor of Ohio, was elected temporary chairman. Hoadly addressed the crowd, then adjourned the convention until 10:00 a.m. the next day, so that the Committee on Credentials could consider certain disputes among the delegates.

At the start of the second day, June 23, the Committee on Permanent Organization announced the roster of officers, including the permanent president, John W. Stevenson

John White Stevenson (May 4, 1812August 10, 1886) was the List of Governors of Kentucky, 25th governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both houses of the United States Congress, U.S. Congress. The son of former Speaker of the United St ...

of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. Before the delegates could formally elect Stevenson, they heard the report on the Committee on Credentials. Two rival factions of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

Democrats had agreed to compromise, both being admitted as a united delegation. A similar dispute in New York was not resolved so easily: Tammany Hall and Tilden's Irving Hall had sent rival delegations as well, and neither was willing to compromise. The committee had voted to consider the Irving Hall Democrats to have been regularly elected; Tammany was consequently excluded. Debate followed, in which some delegates urged compromise, with the idea that a united delegation would help unite the party in New York in the coming general election. The argument was unpersuasive, as the delegates endorsed the committee's decision by a vote of 457 to ; Tammany was banished. Stevenson was then installed as permanent chairman and, as the Committee on Resolutions had not finished writing the platform, the delegates moved on to nominations.

Nominations

The clerk called the roll of states alphabetically. The first delegation to nominate a candidate was California. John Edgar McElrath, an Oakland attorney, rose to nominate Justice Stephen J. Field. Extolling Field's virtues and learning, McElrath promised that, if nominated, "he will sweep California like the winds that blow through her Golden Gate." George Gray, Delaware's Attorney General and a future United States Senator, next nominated Thomas F. Bayard. Gray, in a speech that evinced his admiration for the Senator, said of Bayard: Illinois was the next state to offer a name, as former Representative

Illinois was the next state to offer a name, as former Representative Samuel S. Marshall

Samuel Scott Marshall (March 12, 1821 – July 26, 1890) was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from Illinois.

Early life and education

Born near Shawneetown, Illinois, Marshall attended public and private schools i ...

rose to submit that of his erstwhile colleague, William R. Morrison. Marshall immediately antagonized the South by comparing Morrison to Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, and proclaimed that Morrison's belief in tariff reduction would be a "tower of strength" in the election.

Next, Senator Daniel W. Voorhees of Indiana spoke on behalf of Thomas A. Hendricks, praising Hendricks as a candidate of national unity: " the South, who has been more faithful? To the North, who has been truer? To the East, who has been better, wiser, more conservative and more faithful? And to the West I need not appeal, for he is our own son." The next few states made no nominations. When the roll reached New York, there were cries from the crowd for Tilden, and some confusion when that state's delegation made no nomination.

The next nomination came from Ohio, as John McSweeney made the case for Senator Allen G. Thurman. "Great in genius, correct in judgment," as McSweeney described him in a lengthy speech, Thurman was "of unrivaled eloquence in defense of the right, with a spotless name, he stands forth as a born leader of the people." Next came the Pennsylvania delegation, from which Daniel Dougherty rose. Dougherty, a Philadelphia lawyer, gave a short and effective speech in favor of Winfield Scott Hancock.

As Dougherty finished his speech, delegates and spectators shouted for Hancock. After five minutes, the cheers subsided. Senator Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III (March 28, 1818April 11, 1902) was an American military officer who served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War and later a politician from South Carolina. He came from a wealthy planter family, and ...

of South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, a former Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

general, next spoke to praise Hancock, saying "we of the South would feel safe in his hands", but said that Bayard was ultimately his choice "because we believe he is the strongest man". Richard B. Hubbard, a former governor of Texas and Confederate soldier, spoke in favor Hancock as his state seconded the Pennsylvanian's nomination. Hubbard praised Hancock's conduct as military governor of Texas and Louisiana, saying, "in our hour of sorrow, when he held his power at the hands of the great dominant Republican party ... there stood a man with the constitution before him, reading it as the fathers read it; that the war having ended we resumed the habiliments that as a right belong to us, not as a conquered province, but as a free people." The last few states were called and the nominations ended. After a motion to adjourn failed, the delegates proceeded directly to the balloting.

Balloting

The clerk called the roll of the states again, and a band played "

The clerk called the roll of the states again, and a band played "Yankee Doodle

"Yankee Doodle" is a traditional song and nursery rhyme, the early versions of which predate the Seven Years' War and American Revolution. It is often sung patriotically in the United States today. It is the state anthem of Connecticut. Its ...

" and "Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cover ...

" as the ballots were tallied. The results showed that the delegates had scattered their ballots to a variety of candidates, with no one close to the 492 necessary to nominate (at that time, Democratic conventions required a two-thirds majority for nomination). There was a clear delineation, however, as Hancock and Bayard, with 171 and respectively, were far ahead of the pack. The next closest, Payne, had less than half of Hancock's number, with 81. After one minor shift of ballot, the totals were announced to the delegates. They voted to adjourn for the day, clearing the way for the off-site negotiations that would influence the next day's ballot.

The delegates assembled the next day, June 24, to resume the balloting. Before that could begin, Rufus Wheeler Peckham of the New York delegation produced Tilden's letter and read it to the crowd. The first mention of Tilden's name provoked excitement, but the meaning of the message soon quieted the crowd. Peckham announced that, with Tilden's withdrawal, New York, now supported Samuel J. Randall. Moving then to the second ballot, more than one hundred delegates followed Peckham's lead in voting for Randall, boosting his total to , just above Bayard's 112. But the shift to Hancock had been greater. Before the totals were announced to the crowd, Hancock had gathered 320 delegates to him; as soon as the voting stopped, however, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

changed all of their votes to Hancock. Pennsylvania added those of their votes that were not already for Hancock. Then Smith M. Weed of New York, a Tilden confidante, announced that his state, too, would shift all of its 70 votes to Hancock. After that, according to the party records, "every delegate was on his feet and the roar of ten thousand voices completely drowned the full military band in the gallery."

Nearly all of the remaining states now stampeded for Hancock. When the second vote was finally tallied, Hancock had 705. Only Indiana refrained completely from joining in, casting its 30 votes for Hendricks; two Bayard voters from Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and one Tilden man from Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

were the remaining hold-outs. After the second round was tallied, the nomination was made unanimous. Several delegates then spoke to praise Hancock and promise that he would triumph in the coming election. Even Tammany's John Kelly was permitted to speak. Kelly pledged his faction's loyalty to the party, saying, "Let us unite as a band of brothers and look upon each other kindly and favorably."

Platform and vice presidential nominee

Turning to other matters, the delegates listened as

Turning to other matters, the delegates listened as Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

addressed them with a plea for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. The delegates took no action, and moved on to the platform, which Henry Watterson

Henry Watterson (February 16, 1840 – December 22, 1921), the son of a U.S. Congressman from Tennessee, became a prominent journalist in Louisville, Kentucky, as well as a Confederate soldier, author and partial term U.S. Congressman. A Demo ...

of Kentucky read aloud. The spirit of unanimity continued as the delegates approved it without dissent. The platform was, in the words of historian Herbert J. Clancy, "deliberately vague and general" on some points, designed to appeal to the largest number possible. In it, they pledged to work for "constitutional doctrines and traditions," to oppose centralization, to favor "honest money consisting of gold and silver", a "tariff for revenue only", and to put an end to Chinese immigration. Most of this was uncontroversial, but the "tariff for revenue only" would become a major point of debate in the coming campaign.

Finally, the delegates turned to the vice presidency. Edmund Pettus, representing Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

, moved the nomination of William Hayden English

William Hayden English (August 27, 1822 – February 7, 1896) was an American politician. He served as a U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1853 to 1861 and was the Democratic Party's nominee for Vice President of the United States in ...

, a banker and former representative from Indiana. English, a member of the Indiana delegation, was fairly unknown to most delegates. He had been a Bayard enthusiast and was known as a successful businessman and hard money supporter; more crucially, he hailed from an important swing state. While Hendricks was a better-known representative of Indiana, Easterners in the party preferred English, who they saw as sounder on the money question. Several states seconded the nomination. John P. Irish of Iowa nominated former governor Richard M. Bishop of Ohio but, after all the other states expressed support for English, the Ohio delegation requested that Bishop's name be withdrawn and English's nomination made unanimous; the motion carried.

Aftermath

Keeping with the custom at the time, Hancock did not campaign personally, but stayed at his post atFort Columbus

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

on Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

, in New York Harbor and met with visitors there (as General Grant had in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

, Hancock remained on active duty throughout the campaign). Both parties' campaigns began with a focus on the candidates rather than the issues. Democratic newspapers attacked the Republican nominee, James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

of Ohio, over rumors of corruption and self-dealing in the Crédit Mobilier affair, among others. Republicans characterized Hancock as uninformed on the issues, and some of his former comrades-in-arms gave critical speeches regarding his character. Democrats never made clear what about their victory would improve the nation; Hancock biographer David M. Jordan later characterized their message as simply "our man is better than your man".

Both parties knew that, with the end of Reconstruction and the disenfranchisement of black Southerners, the South would be solid for Hancock, netting 137 electoral votes of the 185 needed for victory. To this, the Democrats needed only add a few of the closely balanced Northern states; New York (35 electoral votes) and Indiana (15) were two of their main targets, but New Jersey and the Midwestern states were also battlegrounds. Early in the campaign, Republicans used their standard tactic of "waving the bloody shirt

"Waving the bloody shirt" and "bloody shirt campaign" were pejorative phrases, used during American election campaigns in the 19th century, to deride opposing politicians who made emotional calls to avenge the blood of soldiers that died in the Ci ...

", that is, reminding Northern voters that the Democratic Party was responsible for secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

and four years of civil war, and that if they held power they would reverse the gains of that war, dishonor Union veterans, and pay Confederate veterans pensions out of the federal treasury. With fifteen years having passed since the end of the war, and Union generals at the head of both tickets, the bloody shirt was of less effect than it had been in the past.

By October, Republicans shifted to a new issue: the tariff. Seizing on the Democratic platform's call for a "tariff for revenue only", Republicans told Northern workers that a Hancock presidency would weaken the tariff protection that kept them in good jobs. Hancock made the situation worse when, attempting to strike a moderate stance, he said "the tariff question is a local question". The answer seemed only to reinforce the Republicans' characterization of him as ignorant of the issues. In the end, fewer than two thousand votes separated the two candidates, but in the Electoral College, Garfield had an easy victory over Hancock, 214 to 155.

See also

* History of the United States Democratic Party *United States presidential nominating convention

A United States presidential nominating convention is a political convention held every four years in the United States by most of the political parties who will be fielding nominees in the upcoming U.S. presidential election. The formal purpo ...

* Winfield Scott Hancock 1880 presidential campaign

* List of Democratic National Conventions

This is a list of Democratic National Conventions. These conventions are the presidential nominating conventions of the Democratic Party of the United States.

List of Democratic National Conventions

* Conventions whose nominees won the subseq ...

* 1880 Republican National Convention

The 1880 Republican National Convention convened from June 2 to June 8, 1880, at the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Delegates nominated James A. Garfield of Ohio and Chester A. Arthur of New York as the off ...

* 1880 United States presidential election

The 1880 United States presidential election was the 24th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 2, 1880, in which Republican nominee James A. Garfield defeated Winfield Scott Hancock of the Democratic Party. The voter ...

Notes

References

Sources

Books * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Articles * * * * * Primary sources * Chester, Edward W ''A guide to political platforms'' (1977) pp 105–10online

Website *

External links

Democratic Party Platform of 1880

''The American Presidency Project''. {{Authority control 1880 conferences 1880 United States presidential election 1880 in Ohio 19th century in Cincinnati Conventions in Cincinnati Political conventions in Ohio Ohio Democratic Party Political events in Ohio Democratic National Conventions June 1880 events